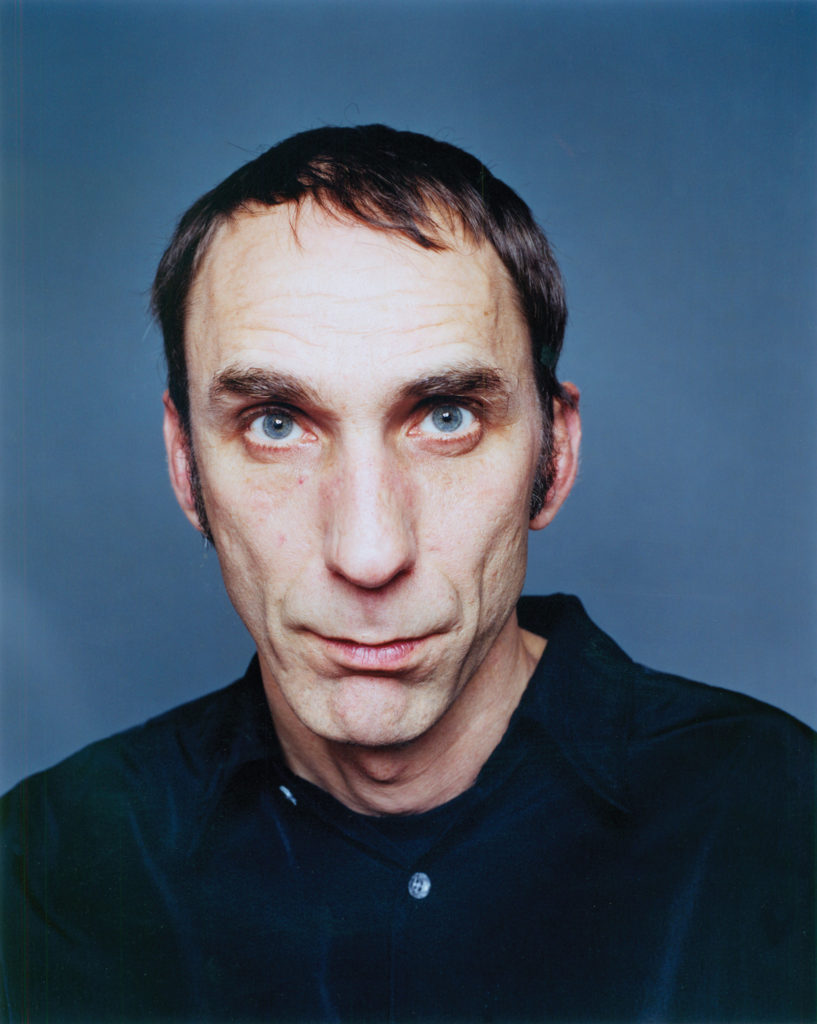

Writer Will Self’s periods of drug addiction are well documented for anyone keen enough to use Google. And anyone familiar with the author should know the best and most public anecdote.

That’s the one about getting caught taking smack on John Major’s private jet.

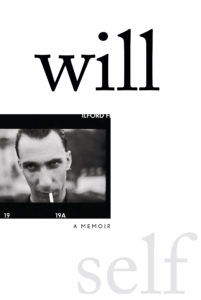

His ‘official’, as I’ll call it, ‘addiction’ memoir only came out at the back end of 2019. ‘Will’, while explicit in it’s account of the writers early life as a heroin addict, is also as darkly comic as the aforementioned incident regarding the then leader of the Tories.

‘Gallows humour’ only ever really works when the subject fights back with guns blazing, which, as the conversation below demonstrates, is certainly the case for the ‘Will’ the modern day Self details so brilliantly within his memoir.

In a lengthy conversation, we discuss the young, educated, pretentious bohemian he ‘lets loose’ in this book, the nature of addiction and recovery, rehab, the recent general election, as well as many other less spoon burning issues. Even our dogs get a mention.

We’re now entering a new year with another Conservative Government. Were you surprised Labour weren’t able to ‘get in’?

No, not at all. I’ve been out and about in the country. I went through some of the so-called ‘red wall’ constituencies when I was writing my diary piece on Brexit for the New European in March. I could tell the mood then was inclined to get behind anyone who’d ‘get Brexit done’, while the Bojo brand remained a vote-winner. His psychic profile perfectly conforms to what the English like to believe about themselves: that they’re insouciant superficially, but contain an inner core of patriotic steel. Also, people really do hate being patronised by a hypocritical metropolitan liberal elite, for whom the downside of globalisation is too much choice at the cheese counter.

Are Labour fucked?

I think liberalism is fucked – and the Labour Party is only the outlier of a much more comprehensive ideological collapse as the climate emergency begins to bite, and the internal contradictions of liberalism. How can you have a viable culture if all sub-cultures, and their values are equally ‘valid’ – become more salient.

Am I right in thinking you didn’t vote?

No – it’s true, I didn’t vote in the general election, the first time I haven’t in forty years. I’m in a safe seat, so my vote really wouldn’t count in a meaningful way. Moreover, I found that when I came to consider not voting, and so stopped having to suspend disbelief in the capacity of our electoral system to factor an myriad little autonomies into one big people’s will, I discovered that I was able to see far more clearly the real limits of my autonomy. In a nutshell: I felt freer.

Will

On writing your memoir – ‘Will’ – where did the need to do so come from?

Well, I’m not saying I did it for the money, but I was conscious when working on my ‘Umbrella’ trilogy of novels, that it was proving difficult to retain readers in this age of almost criminal distraction. I thought the events of my young life, between 17 and 26, actually made a paradoxically gripping – if not ripping – yarn. So I offered the prospect of the memoir to my publishers, who were beginning to look a little askance at the great cascade of fiction emerging from my pen. [So] I was contractually obliged. I’ve been a professional writer, full time, since my late twenties. I’m disciplined, innit.

The book focuses on your early years as an addict. How did you gather material (presumably it wasn’t left to pure memory) to help you write about that time?

I’m a paper maven, and had saved a lot of diaries and correspondence. Coincidentally, I sold all my papers – MSs, letters, notebooks – to the British Library, who kindly indexed them. So had I wanted, I could’ve obtained a wealth of the actualité. In practice, I knew this wouldn’t get me closer to the emotional reality of my life at this time – only estrange me further, hiding it all behind internal arguments about what was verifiable. So I stuck to the feelings and built the scenes around them. My ex-girlfriend, who was with me throughout this period, and who’s also a sort of ‘super-rememberer’, read the text first in typescript, and pronounced herself satisfied with its truth quotient. That was good enough for me.

Did you ever consider writing as a more standard format, more of a ’confessional’, rather than in the third person?

Well, I don’t feel I have anything much to ‘confess’. It was all mostly in the public domain already, and besides, a confessional implies [there’s] someone to confess to. Those who believe they should shrive themselves in front of the reading public are almost as misguided – in my view – as those who believe the entire universe to be a sort of giant real-time moral computer game, in which a bizarre entity creates myriad avatars to see if they can fulfil his creepy ethical programme. As to objectivity – every piece of writing requires a healthy dose, if it’s available. I feared that if I identified too strongly with my young self, I would be dragged into the same pathological mind sets as characterised that lethal period of addiction.

As you say, you ’created this character’ and ‘set him running’. What did writing like this bring to what you were trying to say?

A different kind of sympathy, actually, more empathy: an ability to intellectually appreciate the sate this young man was in. I hope that high-toned realism has translated to the page, and the readers do, paradoxically, experience this memoir as being more real than those written using more conventional structures and stratagems.

I would say, for any writer, there are no places you shouldn’t try to go to. Is that fair for you?

Absolutely. Like the Beast himself, do what you will has to be the law of the serious writer.

On revisiting the darkest moments in ‘Will’ – did going through this process have any effect on you or at least take you back to places you’d rather bury?

I think it’s always a mistake to write with any kind of catharsis in view and I certainly didn’t sit down to write this book believing it would make me feel any better about anything. In truth, I’ve been reconciled to my addictive illness for years now and yes, as I’ve said elsewhere, there may not be anything funny about heroin addiction, but quite a lot of the things junkies get up to are funny, albeit in a very dark way.

Back to ‘The Beast’. You start ‘Will’ with a quote from Aleistar Crowley. He’s someone who I’ve always regarded as a dull, spoiled, and generally overrated so-called poet. You were reading about smack addiction before you lifted a needle. Presumably as an impressionable, young, pretentious type as you admit you were, this was a guy who you wanted to emulate? or William Burroughs…

Not Crowley in particular – much more Burroughs. The episode in the memoir is intended to underscore the strange feeling we had in the early 1980s that this heroin culture pre-existed us by a long time. In fact, I rather agree with you about Crowley – who was faintly ridiculous, as much as anything else. I’ve never actually read the whole of his ‘Diary of a Drug Fiend’. From what I have, on sag-bags in squats, over the years, it’s deadly boring. But I did read his ‘Autohagiography’ and found that rather amusing. He’s really a heterodox late Romantic like Augustus John or Eric Gill, rather than some great necromancer. But apropos the latter: addicts, since they feel themselves to be the puppets of numinous forces, often indulge in a great deal of magical thought, so it’s Crowley the magician they reverence, quite as much as Crowley the junky.

“Self is a perpetually rewritten story”. Is it fair to say that, more or less, it’s impossible to really recall one’s own earlier moments, that writing about the past is just the current ‘self’s’ own version? I suppose I’m thinking about Milan Kundera’s own writing.

Kundera certainly says something like this and it also seems confirmed by recent studies in neuroscience, that appears to show the human mind/brain as being equivalent to Theseus’s proverbial ship. I’m sure I haven’t really managed to avoid this problem – how could I? But I do feel my monoperspectival narration of ‘Will’ may have allowed me to sidestep the more egregious examples of this – simply by not basing the memoir on incidents that I believe I recall, but rather on the emotional atmosphere surrounding my quotidian life during this period.

My greatest vice is a liking for alcohol rather than the full ‘ism’ (others may disagree). What does an addict do to prevent relapse and has this changed from when you first quit to getting older?

It’s hard to say. It’s not a one-size-fits-all. Certainly, the underlying assumption found in the 12 Step Anonymous fellowships, and which also lies behind the Hazelden school of rehabilitation that was practiced at Broadway Lodge in Weston-Super-Mare (where Will attends rehab), has it’s core the idea that complete recovery is never possible. That’s why the denizens of ‘the programme’ as it’s known, always refer to themselves as ‘recovering addicts’ and ‘recovering alcoholics’. They also – apropos your own issues – make no distinction between any form of chemical dependency – booze, smack, it’s all the same: their credo is that the addiction resides in the individual, not the substance. I think things are a little more complex, and that neither a reduction to the chemistry, or an elevation to some medicalised psychiatric model will suffice. Nor again, do I find the 12 Step programmes’ characterisation of addiction or alcoholism as a ‘spiritual’ malaise altogether satisfying. Rather, it seems to me that lasting recovery, just like not falling into addiction or alcoholism in the first place, probably rests on a sort of tripartite relationship between social, psychological and existential forms of security. Some of this – for addicts who’ve fallen right through the nets of society – can be reconfigured in the fellowships, but ultimately long term recovery rests on a new calibration of self and society.

I wasn’t around in the 1970s, for only a few years in the 80s, in oblivious infancy, and I was alarmed to find out about the existence of a group such as the Paedophile Information Exchange. Tell me about them and the overall ethics of that time.

The 1970s were a wild and woolly time in terms of public ethics and private morality. The cultural revolutions of the 1960s seemed to many to’ve torn up the rule book (and arguably, behind this lies the reevaluation of all values implied in the Holocaust and the atom bombing of Japan – something I’ve explored extensively in my fiction). There wasn’t just that ‘goggle-eyed loom’ Jimmy Savile hiding in plain site on Top of the Pops, there were also, at left wing fringe meetings, the Paedophile Information Exchange, who’d set up their trestle table like the vegans and the hunt saboteurs, and lay out their leaflets. These had titles like ‘The Case for Man-Boy Love’. We did at least consider it potentially that people should be allowed to have sex with children, but then we were children! What the adults were up to in all of this is neglect. My brother and I ran wild in childhood and adolescence and we certainly weren’t the only ones. It’s out there in the wilds that the noncing takes place.

How much did that time generally influence your path?

I certainly think the great brown wave of smack that engulfed our island nation was understandably congenial to psyches already strung out on the great glaucous wave of amphetamines (yellow sulphate mixed with blues) that preceded it. But I suspect there was a great capacity for self-destructive behaviour in me already. Will, in the memoir, is self-harming by slashing his arms with razors by the time he’s ten, and graduates to burning himself with cigarette ends as soon as he starts smoking, around twelve.

Am I correct in detecting your distain for the ‘Will’ character? (descriptions like ‘snivelling smackhead’)

I think you’re committing one of the fundamental misreading of my book – in line with those critics who sought to conflate me, now, with a third person impersonal narrator that doesn’t really exist within the text. It’s ‘Will’ who labels ‘Will’ a ‘snivelling smackhead’. What I wanted to try and do with the book was express the sheer amount of self-hatred the very average addict experiences in any given day. I was – relatively speaking – well brought up, and had a decent conscience. Inasmuch as I embraced the junky life, I was equally repelled by my own deformations of character.

Apologies if I’m way off the mark, but to me, the character ‘Will’ come across to be something of a Cunt.

Again, I strongly dispute the idea that the Will described in the text is a cunt. Unless you subscribe to the idea of original sin, what you’re looking at here is a child – yes, at seventeen you’re still a child – falling victim to mental illness. What does he do that’s so cuntish? Two time a girlfriend? Drive dangerously? Deal drugs a bit? Have envious thoughts? I suggest you examine your own conscience and behaviour a little more strenuously before you chuck such aspersions about so liberally. Freud observes that everyone feels OK about having done bad things they’ve got away with – perhaps my real crime here is not to let my younger self get away with it?

In the spirit of ‘What would you say to young Willy should you meet him now’ – Does being lecturer go any way in helping others avoid the mistakes you’ve made?

I’ve lectured at Brunel University for the past decade – but it’s also bringing up four children that hopefully might help me to be a steady, consistent and emotionally intuitive enough presence in young people’s lives to help them avoid the very real pitfalls of drug use. However, I wouldn’t bet on it. Some young people are so lost, so unhappy – I was one – that short of physically interposing yourself between them and the substances they’re abusing, there’s little you can do. Of course, I used to wish my own parents had done just this – rather than being so dégagée.

And the ‘seamless and Sisyphean go around’ of addiction. Is addiction itself a mental illness which one must ‘break out of’?

Again – it’s the Will in the book who describes it as a ‘Sisyphean go round’, but I’d agree with him. There’s a certain point in true drug addiction when you cannot break the cycle, and that is the true point of madness, after which recovery becomes a slow and elusive business.

You’ve spoken about your obsession over sanity. Do you think sanity is subjective?

‘Subjective’ is a lazy ascription in this context but I’m enough of a Laingian, still, to believe that the line between sanity and insanity is defined by social convention as much as objective reality. Nonetheless, as someone who’s shared houses with flamboyant schizophrenics, I can tell you that madness does very much exist. I certainly feel myself to be someone who’s recovered – to some extent – from quite severe mental health problems, but as I’ve intimated above, there’s no simple way of explaining how to do this.

In ‘Will’ you talk about yourself being a ‘A badly designed robot’, ‘On the job’ as a working junkie at IBM. It’s not in keeping with the typical view of junkies being permanently ‘on the dole’…

I came from a family with a strong work ethic. I only signed on for about a month during my first period of active heroin addiction – and during my second (1989-99) I wrote and published ten books. Not all addicts are unproductive, and in my second phase of addiction, writing definitely became my drug of choice!

Talk a little about the criticism or praise as you’ve had a lot of both through your years as a writer.

Praise and criticism are always about the ego – inflating it, deflating it, paradoxically inflating again (for those of us who’re masochists); none of this is of any use to a writer who aims to be original – and, to perform acts of creation akin to parthenogenesis. In all honesty, I’ve never read a single thing in a review of one of my books that told me either how to write better, or how to be a better person.

The Cuckoos Nest

I thought I’d lost something as I listened to this book rather than reading but in truth, I would have lost something by reading it. Mainly, the comic theatrics in your voice on the audio is very funny throughout…

The comedy is intentional – and I’ve always ‘done the police in different voices’. I’m glad you enjoyed the audiobook version – as people read less and less, it’s back to the oral in order to reach any kind of future for the novel.

Can you speak more about your time in rehab?

It was the car crash described in the memoir that got me into rehab. I’d literally as well as metaphorically hit the buffers, with too many debts and no means of paying them. I had no great hopes for recovery at the time and I felt completely eaten up by my addiction and hollowed out. But I also loved my mother and I could see that my addiction was killing her. I went to rehab for her, really.

And on the subject of extreme onanism? 17 times in one day is remarkable.

Yes, well, people wank… people over-work… people get fat… people smoke too many cigarettes… people become addicts of just about everything once their drug of choice is denied to them, but they haven’t managed to resolve the issues that made them compulsively use in the first place. I certainly fell victim to all of these secondary addictions and more during the two years I stayed clean in my late twenties. When I got clean again in my late thirties, things were different.

Were you always against the notion to write a ‘Cukoos Nest’ type novel about your time in the rehab? But then you don’t have much time for the autobiographical novel?

Yes, I never wanted to write a rehab’ book like that – and I didn’t have much time for an autobiographical novel; I think there’s something disingenuous about not admitting to being your own protagonist. Anyway, no one needs to write an autobiographical novel if they’re true to their own psychic experience – because that’s where the truth is, not in mere facticity.

‘Will’ ends when you’re still in your mid 20s. Presumably there will be a part 2, ‘Self’?

I have a couple of other books I want to write just now, but who knows.

You end the book with: “The Will of the future is a ghost… and you can see right through him.”

It was partly a joke about the fact that the text is very obviously written by me but yet I’m absent from it. Really it built off the serious point about my relationship to my dead friend, Hughie. The world – as Wittgenstein said – is ‘everything that is the case’; and it’s certainly the case that I’ve thought about poor dead Hughie far more and for far longer than he ever thought about me, and I do think this makes him – in an objective sense – realer than I am.

The Internet, Kafka, Shooting Stars and Morrissey: A Post-Christmas tale of ‘Will-Self’ Indulgence

What was Christmas look like for you – you don’t strike me as a man who would be festive?

As the father of four recently bereaved young adults, it was never going to be a great one this year and I’ve never held a candle (!) for the festival overall, but nonetheless, as a family minded man, I can see both the virtue of the occasion – and it’s horrors. I’m not too bothered by material gifts. If the entire British population could promise not to make mobile phone calls on public transport for a year that would be… nice.

I don’t have kids, only an eight-month-old King Charles Spaniel who does require walks and cuddles, that was Christmas for me..

I, too, have a dog… but an elderly and cantankerous Jack Russell. Curiously, though, he also requires cuddles, although not as many walks as formerly due to bad arthritis.

For a writer, I’ve heard you say there needs to be a level of anonymity. How is that possible in a world like today, the constant presence of the internet, being online etc.

You can still sit a café and eavesdrop on the conversations of people sitting behind you – this is an exercise I always encourage tyro writers to undertake. It puts them back in touch with the immediacy of reportage (which good fiction always is), and with the incredible disjunction that occurs when people try and turn ordinary speech into ‘dialogue’; of course, an analogous process occurs with descriptive prose. All of which is by way of saying: the art of writing is unaffected by the internet – it’s the novel and the novelist as cultural institutions that have inevitably lost their centrality.

Will the internet destroy us eventually?

In a sense, it already has. It’s inverted human social formations more than ever heretofore has been done by exiting mass pressures. It’s created Marshall McLuhan’s global village, but it’s turned out to be a village of the damned. It’s allowing for classical liberalism to accelerate to it’s logical end point of full contradiction between individual autonomy, and the rights of others, and of course the infrastructure alone is estimated to account for 6% of current global heating – with no obvious dividend in terms of greater production. But then again, for our current perilous situation, we could just as well blame cars or trains or planes or coal fires.

Which brings us to the real ‘unbearable lightness’ of being a prawn cracker. What is your immediate memories of being on Shooting Stars?

I enjoyed doing the show a lot. It was amazing to work with proper comedians, especially physical ones like Jim Moir and Bob Mortimer. I learned a lot from them, not least that if you want to look brilliantly on television, make sure your fellow performers’ best bits end up on the cutting room floor. I also enjoyed working with Matt Lucas and Johnny Vegas – both lovely men, and brilliant performers who’d start riffing off the studio audience long before the cameras rolled. And as I’m sure you realise: inside the breast of every true Englishman beats the heart of someone who rejects the crude equation between sex and gender – so I hugely enjoyed dressing up as Britney Spears.

I first became interested by yourself in an old documentary called ‘The Importance of Being Morrissey’. As someone who has been subject to unfavourable criticism, how do you feel about the levels of vitriol thrown Morrissey’s way in the press?

Well, he has gone quite hard to the right – and he doesn’t seem to feel the need to modulate his remarks in anyway. While I don’t really agree with much of what he says – I do have a grudging admiration for anyone prepared to outrage public opinion in these conformist-populist times.

Finally… Franz Kafka, with whom I share a long standing admiration. What maintains your own interest?

He’s one of the greats – no question. And as with the true greats, I find I discover more and more in him the more I reread. Recently, on a train ride, I began rereading the Zurau aphorisms, and found myself laughing out loud. For years I struggled to find the humour in Kafka at all – but now I see it: it’s a kind of sublime comedy of psychic slapstick. As Michael Hofmann puts it in his brilliant ‘Introduction to The Metamorphosis’, Kafka specialises in identifying the calibration of events, and displaying the almost infinitely infinitesimal rates of change that typify the involutions of human thought and being. As Kafka puts it ‘the decisive moment for all humanity is always to hand…’. Which is tragic – but also… ridiculous!